The Holocaust

“Kinderblock” – The Children’s Block

After a short period, we were ordered to join with other children and youth, and move to the “Kinderblock”, the Children’s Block. That was a most frightening order, because the “Kinderblock” was an infamous facility. As long as the gas chambers were in operation, that block served as a warehouse of humans. Whenever the numbers of those delivered to the chambers did not reach their full capacity, children of the “Kinderblock” were taken in order to fill the quota. The man in charge of the block was a Ukrainian or Byelorussian by the name Oleg, whose cruelty was well know all over the camp. Nobody could change the ruling forced upon us. We were transferred to Block 29, the Children’s Block, well aware of and horrified by our separation from dad, who remained in the central section of the camp. Shmuel and I were overwhelmed by an indescribable anxiety.

Within the block, atrociousness and harsh conditions ruled all over. There was no food, and sick and dying children surrounded us. Every morning, dead bodies of boys were lying next to us. Others used to take off their clothes and steal their belongings, and the dead were left naked on their bunks. First thing every morning was the removal of the dead bodies from the barrack. The only advantage was that the counting of the inmates took place inside the block, and we were not pushed to the daily Appells outside.

There, at the “Kinderblock”, was our first time to face all alone the reality of dread and terror. Once – we never knew in what circumstances – dad came over to the hatch of our block. He told us that he was to be deported out of Birkenau, and said good-by. He looked into Shmuels eyes, and Shmuel understood that from now on he was the person in charge. While in Sered, at the time dad was out of the camp, even though we were together with mom, he already experienced the responsibility of being the head of the family. However, in Birkenau the situation was entirely different. Our parents were no longer with us, and Shmuel was the person in charge. Probably, that sense of responsibility gave him strength to take care of his younger brother, instead of digging into his own soul. Retrospectively, Shmuel has confirmed that feeling, which helped him overcome hours and days of despair.

We were convinced that we arrived at the end station of our lives. We could not be sure that killing by gas has stopped, and we had no idea that the Germans began concealing any evidence of the crimes they committed.

The sense of responsibility was not easy for Shmuel. As all the thefts took place at night and those in a deep sleep were the first ones to be robbed, he was afraid of falling asleep. After all, he did not want to wake up in the morning and see that the little we had disappeared forever. We were neither among the full-bodied boys, nor among the small children in the block. Many youngsters were bigger and stronger, and they took advantage of their strength in order to terrorize the others, particularly as time went by and there was less and less food at our disposal, and more children fell ill. The block was crowded to its rim, and every day brought new battles for life and death. Yelling, cursing and beating were the prevailing factor in a very unpleasant atmosphere. We sat all day long, day after day, starving and doing nothing. To our luck, Shmuel and I were relatively well off. After all, we joined the block later than many others who were already exhausted from their long stay in it.

Because of the difference in our age, we also differ in our memories of the “Kinderblock” in Birkenau.

Shmuel: One of the most shocking experiences was my first encounter with sexual deviation, which I witnessed in the camp shower, located out of the block. The latrine was adjacent to the shower. As I mentioned before, taking care of our cleanliness was one of our family’s rules. Although water was ice-cold, we strictly observed these rules, and took shower at any given opportunity. At the same time we also washed part of our clothes, and because we had no other sets of clothing we washed either the shirt or the pants, and wore them all wet.

I did not know what those other men actually did, but I heard the screaming and saw the disgusting sights, which frightened me thoroughly. Although I was never threatened or exposed to any danger, I grasped more or less what was happening, and what I saw did not seem to be normal.

Naftali: To me, the “Kinderblock” in Auschwitz-Birkenau was the most extreme torment I had until then. Without our parents we were all alone, exposed to very difficult experiences. There and then, the most troubling question began to bother me: Does God exist? If God exists, where is He? I remember being alone in the latrine; I wanted to test God’s existence. I began cursing him because I wanted to test whether He could hear me, if he at all listens to children. To tell the truth, I felt quite panicked in the light of my daring test. Upon leaving the latrine I realized that nothing happened and nothing changed. At that very moment I lost my belief in God, and all I sensed was loneliness and fear, as if the whole world was falling apart.

Inside the block, one of the most horrifying phenomena was the matter of hygiene and toilets. It is difficult to describe how much suffering I had to go through whenever I wanted to relieve myself. At the end of the block, almost outside of it, there were cans over eighty centimeters high, all messed up with faeces with a horrible smell. Every night, in the terrible cold, I walked – sometimes barefoot – over to those cans, and so did most of the boys (after all, who did not have to relieve himself?). That was hell!

There were people beyond their breaking point who decided to commit suicide. Night by night I was shocked by their screaming, until they died.

On that spot we got our first lesson on “business” in food. There were women behind the high-voltage wire fence, with whom we exchanged bread for onion. Stretching our arms between the wires was most frightening. Even now, over fifty years later, whenever I eat onion, the picture of the fence appears in front of my eyes.

Another, very personal experience comes to my mind. In the Sered camp there was a family, who in Bratislava were our parents’ close friends. Their daughter, Marika Rab, was my girlfriend since our days in school. She was a very cute and beautiful, a bit round and overweight girl. Her age was eight, and I liked her very much. Close to the time of deportations, our friendship has strengthened. Marika and her parents were sent to Auschwitz before we were deported. There, in Birkenau, right upon our arrival, I was surprised to have seen her. She walked in a rank with her mother and other women in the opposite direction, to a destination I would not know. Where they taken to the crematorium? I do not know whether they saw us, but for me it was the last time I caught sight of her, and only the memory of Marika stayed with me for the whole life. Not once I thought that if she had been saved, perhaps our friendship would have developed into a serious relationship. To my deep sorrow, she did not survive those days of horror.

|

|

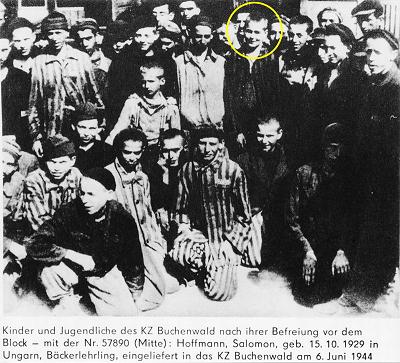

Buchenwald childrens on the release day. Naftali Furst is mark in a yellow circle |