The Holocaust

Buchenwald

At the end of our journey, the train entered a camp on a sidetrack, which was built for one purpose: unloading new inmates. The name of the camp was unknown to us; only later we learned it: Buchenwald. As we were introduced into a large, well-lit hall, we were pleasantly surprised, because the conditions there seemed to be much better than on the train. Even the tone of voice and the attitude to us gave the impression of a different pattern. When, despite our plea, all our clothes were taken away, we were told not to worry. After a while, we really got another set of wear.

The next step was registration. We thought that our personal data have been transmitted from Birkenau to the Buchenwald authorities, but that was not the case. Each one of us got a new number, clothes in a reasonable condition, and a cap. As each category of inmates had a specific marking by certain colors, we too were marked. Our mark was a black-red star, which meant “Political” and “Jewish”.

We were taken into a huge barrack, full of inmates who came to Buchenwald before us, people of all ages and all countries. We were placed on the top floor of the bunks, namely the fourth floor. The barrack was dark and gloomy, filled with an atmosphere of hopelessness. Our physical condition was already poor. I was very weak and sick. Shmuel’s toes froze. There was almost no food, and the thefts among the inmates were unbearable.

Three weeks later, new selection for deportations had begun. Nobody knew of their destination. Then came the day, at which we were separated from each other. Until then, we always did our best to stay together, but on that day we were helpless. In the course of the day we learned that there are two other brothers in the same barrack who faced a similar problem. The older of the two suggested to Shmuel that they exchange their names and identities, so that each one of them would stay with his brother. We accepted their proposal, and allowed them to decide whether they wish to stay in the camp or leave it by the next transport. Following a long wavering, they decided to leave the camp. That decision determined their fate to death, and ours to life. Towards evening they were taken to the railway station in the town, and loaded onto the wagons. Later in the evening, the Allies bombed the train station, and all men on the wagons were killed. We also heard that some of those who were not killed by the bombs tried to escape, but the Germans shot them to death.

Shmuel: From that moment on I had a new name. It began with a “Sh” and sounded like Stern or Strauss, but I cannot remember it now..

Buchenwald was a detention camp for political inmates. There were no children in the camp. The underground was an integral part of the camp. It had a special status, and as such it negotiated with the Germans. It is not to say that the latter got any dictates, but they understood that everything was a matter of “give and take”, and the underground could not be ignored – certainly not at the end of January 1945. At that time, following pressure exerted by the underground, a separate and secluded barrack for children was established.

Duro was transferred to the children’s barrack, Block 66. As I was registered under the name of the other guy who upgraded his age to seventeen, I was sent to Block 49, instead of the children’s block. To my great sorrow, we were set apart. People around tried to console me, but I was unable to calm down. I always tried to locate Ďuro, while – as I later learned – he was looking for me.

One day, people called: “Where is Peter Fürst? He must report immediately!” Upon hearing my name, I dug myself deep into the cell, but they kept calling “It’s okay, you can come.” I was afraid that my deceit, i.e. changing my identity, has been discovered, and did not dare to come out. When I did not follow suit, they gave up their search and left. Two days later, people were again looking for me. Upon encountering some other boys, they portrayed my looks and said that they would take me to my brother. After a long faltering I reported to them. A Polish man came over and began caressing my head and comforting me. He said: “I understand that at my previous visit you did not report. Your younger brother is waiting for you. Come with us.” Later I learned that the man was appointed by the underground to take care of the children, and he became their “dad”. I reported to the person in charge of the block. He promised to settle the matter of the exchanged names. I left Block 49 and moved to Block 66, the children’s barrack.

There I met Ďuro. We were happy to be together again. Over 900 children lived in that block. Though it was overcrowded, the conditions were better than in the rest of the camp. The food they got was the same, but there was more fairness and preciseness in its distribution. In terms of personal hygiene, such as washing, haircut, etc., care was taken of the boys. In the evening, the barrack was heated. At some evenings the children were assembled; information was given to them on current events in the world and the ongoing war. Those events were arranged by a well-organized institution, which also encouraged the boys to keep their morale high. They even introduced community singing.

The barrack was divided into two parts: one half consisted of Polish boys, while the other half comprised children for other countries. We were together with Hungarian children. They had a terrible habit: all day long they loudly fantasized about food, each one telling what kind of meals his mother used to cook and bake: cakes with whipped cream or poppy seeds, and much more.

The daily Appell took place inside the barrack, and the boys were protected from standing in the outside mud, exposed to freezing winds. That was a great achievement.

At that time, Ďuro’s health has gradually worsened. He got pneumonia, coughed incessantly and suffered from high fever. I was disparate and frustrated because I could not help him. The men in charge of the block decided to transfer Ďuro to the local hospital.

Only once was I allowed to visit him there. I was glad to have seen him in full consciousness, because at the time he was taken to the hospital I thought that he would not survive his illness, and I would never see him again. He even gave me a loaf of bread.

After that visit, our routes took different courses. We met only after the war, in Slovakia.

|

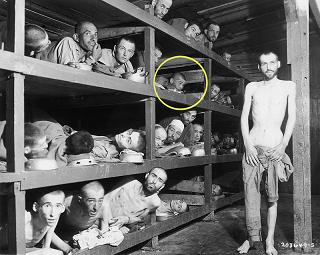

| Buchenwald. Naftali Furst is marked with a yellow circle |